The Münchhausen Trilemma: Why Proving Everything Is Like Pulling Yourself Out of a Swamp by Your Own Hair

|

|

Time to read 5 min

|

|

Time to read 5 min

Why is absolute certainty so hard to achieve in philosophy, and what does a German baron famous for tall tales have to do with it?

How does the Münchhausen trilemma challenge our fundamental assumptions about knowledge and truth?

What practical implications does this philosophical puzzle have for our everyday thinking and decision-making?

Have you ever been stuck in one of those endless "but why?" conversations with a particularly persistent five-year-old? If so, congratulations! You've experienced a version of one of philosophy's most enduring and annoying puzzles: the Münchhausen trilemma.

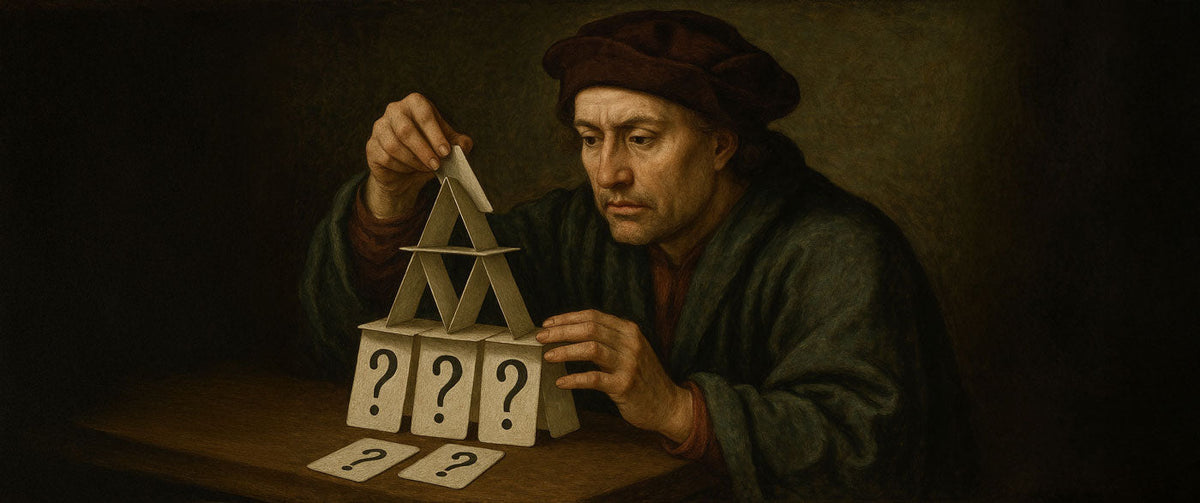

Named after Baron Münchhausen, an 18th-century German nobleman famous for telling outlandish stories (including one where he escaped a swamp by pulling himself up by his own hair), this trilemma captures the seemingly impossible task of providing an ultimate justification for any knowledge claim.

As philosopher Hans Albert, who popularized the term in the 20th century, put it: "If one demands a proof for everything, one will also demand a proof for the premises of every proof. This leads to a situation with three alternatives, all of which appear unacceptable."

So what exactly are these three alternatives? Let's break them down with all the philosophical gravitas of a sitcom explanation:

When someone asks you to justify a claim, you provide a reason. But then they ask you to justify that reason, and then justify the justification of that reason, and so on... forever.

As David Hume, with his characteristic Scottish blend of insight and exasperation, noted: "In every system of morality... I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning... when of a sudden I am surprised to find that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought or ought not."

Translation: At some point, everyone hits a wall where they can't justify things further, but just try getting them to admit it!

This option involves using your conclusion as part of your premise. It's like defining "cool" as "having the quality of coolness" and then feeling smug about your lexicographical prowess.

As Ludwig Wittgenstein might say (while giving you a particularly withering stare): "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." In other words, we're often trapped in circular reasoning by the very structure of our thinking and speaking.

Finally, we could just accept certain basic assumptions without proof. These are sometimes called "self-evident truths," "first principles," or as I like to call them, "philosophical get-out-of-jail-free cards."

Aristotle, the original academic know-it-all, defended this approach: "It is not possible that there should be demonstration of absolutely everything; there would be an infinite regress, so that there would still be no demonstration."

René Descartes thought he'd cracked this nut with his famous "I think, therefore I am." But as soon as he tried to build on this supposedly rock-solid foundation, the philosophical community collectively said, "Nice try, René, but we have follow-up questions."

The trilemma isn't new – ancient Greek skeptics were already annoying their fellow philosophers with it over 2,000 years ago. Agrippa, a skeptic philosopher, formulated "Five Modes of Skepticism" which included the core of what we now call the Münchhausen trilemma.

Fast forward to the Enlightenment, when philosophers became obsessed with finding absolute certainty. Immanuel Kant tried to resolve the trilemma by distinguishing between analytic and synthetic knowledge, essentially saying, "Some things we just know are true because of what the words mean, okay?"

Karl Popper, in the 20th century, took a more pragmatic approach, suggesting that while we can never prove a theory with absolute certainty, we can at least falsify incorrect ones. As he put it: "Good tests kill flawed theories; we remain alive to guess again."

You might be thinking, "This is all very interesting, but I'm not a philosopher, and I have actual problems to solve." Fair enough, but the Münchhausen trilemma has real implications for how we approach knowledge in everyday life.

Consider science, which many see as our most reliable source of knowledge. Yet even science rests on unprovable assumptions about the uniformity of nature and the reliability of our observations. As physicist Richard Feynman quipped, "Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts."

Or consider political debates, where people often argue from fundamentally different starting assumptions. No wonder we can't agree on anything – we're stuck in different versions of the trilemma!

So what's the takeaway? Should we all become extreme skeptics, doubting everything and living in a state of perpetual philosophical angst?

That seems a bit dramatic. Instead, perhaps we can learn to be more aware of our epistemological limitations without becoming paralyzed by them.

As William James, the pragmatist philosopher, suggested: "The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook." Sometimes, the wisest approach is to acknowledge the Münchhausen trilemma as a theoretical problem while making practical judgments based on the best evidence available.

Or as contemporary philosopher Daniel Dennett more bluntly puts it: "There's nothing I like less than bad arguments for a view that I hold dear."

The Münchhausen trilemma gives us all a kind of philosophical wedgie – uncomfortable, a bit embarrassing, but ultimately a humbling reminder of our human limitations.

We can't escape the trilemma entirely, but we can learn to live with it more gracefully. Perhaps that means being more transparent about our assumptions, more open to revising our beliefs, and more charitable toward those who start from different premises.

As Socrates, the OG philosophical gadfly, reportedly said: "I know that I know nothing." And if that's good enough for Socrates, maybe it can be good enough for us too.

So the next time you find yourself in an endless "but why?" conversation, you can smile knowingly and say, "Ah, I see you've discovered the Münchhausen trilemma!" Then prepare to explain what that means for the next hour or so. You're welcome.

The "Münchhausen Trilemma" is named after a baron who claimed to pull himself from a swamp by his hair

This trilemma shows why proving all knowledge is similarly impossible

Knowledge faces three dead ends: infinite regress, circular reasoning, or unprovable assumptions

The trilemma doesn't mean we should abandon the pursuit of knowledge, but rather embrace a more nuanced relationship with certainty

Though ancient in origin, this concept helps us approach knowledge claims with appropriate humility

You liked this blog post and don't want to miss any new articles? Receive a weekly update with the best philosophy memes on the internet for free and directly by email. On top of that, you will receive a 10% discount voucher for your first order.

Your cart is currently empty.