Rock the Convent: Hildegard of Bingen's Concept of Veriditas

|

|

Time to read 10 min

|

|

Time to read 10 min

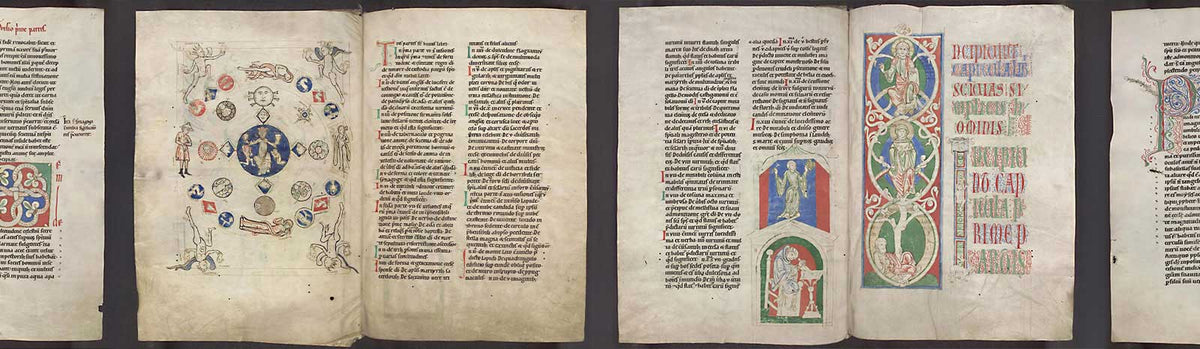

Medieval manuscript pages from Hildegard of Bingen's "Scivias," courtesy of the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.

Who was Hildegard of Bingen and what was her role in the Middle Ages?

What is veriditas and what can it teach us about health and our own well-being?

What can we learn from Hildegard of Bingen outside the medieval convent?

Hildegard of Bingen (1098 - 1179) made her mark during a time when women had few methods of raising their voices. A polymath of epic proportions, Hildegard was one of the biggest names in the mystic movement of the Middle Ages.

It is the 12th century in what would now be called Germany. A girl gets sent off to a convent to be trained in the religious life. She dedicates her life at an early age to God. She trains under an older girl, then makes her way to a convent she will eventually run. Later, she will start up other convents. She’s killing it over here.

To the uninitiated, convents seem to be a simple life, dedicated to prayer and fasting and silence. Many of us may have seen “Sister Act,” and watched with horror as Whoopi Goldberg’s character has her crummy looking dinner ripped away from her for talking too much.

In truth, it’s a lot more complicated than that. Monastic life in the Roman Catholic tradition has its roots in early Christianity. Stories exist of hermits who ran off to the desert to live lives like John the Baptist, a Biblical figure who was known for subsisting off locusts and honey for his daily noms.

By the 500s AD, you’ve got a bro called Benedict of Nursia writing a rulebook about monastic life. The Rule of St. Benedict, as it is called today, sets the stage for daily living of both monks and nuns in religious communities. Known most famously for its three vows: poverty, chastity, obedience, the book details the strictness and structure that comes with running and living in a community of people who decide to commit their lives to their faith.

As in Hildegard’s time, taking on a monastic lifestyle separated the monk or nun from the rest of the world, literally sectioning them off into small communities, or cloisters. Though such communities followed the Rule, there was much room for interpretation, and so orders of monks and nuns soon popped up.

The Franciscans, for instance, followed the simplicity and piety of St. Francis of Assisi (c. 1181 - 1226, after whom the last pope was named), ditching their possessions and running around in pious poverty. The Dominicans, followers of St. Dominic (1170 - 1221), were talented in writing sermons and preaching. Over time, more and more orders would be established.

The Middle Ages was a peak for religious life, as sending a child to the monastery or convent might have helped elevate the child’s education, given young women an alternative to married life, and eased up the family expenditures, as the person would be taken care of by the religious community. As such, women who became nuns in convents developed a certain clout that they would not have had outside the religious life.

In the Middle Ages, women were by no means in some sort of feminist utopia. Writers such as Christine de Pizan (1364-c. 1430) might be considered proto-feminists, but women themselves were not given much of an honored place in society, given their relation to Eve and some other patriarchal religious notions at the time.

However, in this period before the Renaissance and Modern periods, it could be argued that there was a bit more social mobility for women due to the fact that, in places in Europe, they could own property and manage their own business affairs , and convent life also offered an alternative to being trapped in a marriage and expected to bear and care for children.

Later, especially as a result of the Protestant Reformation, women would be expected to be subservient to their male spouses, and in many places would not be allowed to own property. For those in power of the Protestant faith, the convent or monastery would never be an option, as both were done away with in the newer faiths. Childbearing and obedience to the husband became the expected norm.

But we’re in the 11th century again, and Hildegard of Bingen just started to have a headache.

So, we have this nun traipsing off to her convent. It is not long before she starts receiving visions from the Man Upstairs. These visions happen in the form of blinding, scorching visuals, a debilitating headache, and some words from God himself. Encouraged by a supervising monk, Hildegard, now an abbess, or leader of the convent, has them transcribed.

She dictates them to an assistant, and begins to create very distinctive artwork surrounding them. It’s incredible, very taxing, but it helps give her inspiration for her other work.

When you are guided by the hand of the Big Guy himself, you become unstoppable. In recording these visions in her body of work, Hildegard takes some time to offer up some of her own philosophy and medical advice. She is known as a healer, and takes her medical advice seriously, with a sort of gestalt view, well before gestalt was a thing.

But why stop there? Advising and helping people with their medical issues, getting visions, and making artwork is not enough! Hildegard also composes what is arguably called the first opera, as well as a plethora of music that is still played and recorded today–some of the most recorded of that era.

This mother superior is rocking it, and soon becomes an influential figure outside of the scope of her convent in Disibodenberg. She starts correspondences, including with the pope. In these letters, she consistently refers to her feminine weakness, to her humility and lack of education as a woman. She humbles herself. But then she chastises the pope, referring once more to her visions from God, which help legitimize her, as well as her consistent insistence of her womanly ignorance. Put them together and she becomes a force to be reckoned with.

During her time as a mystic, Hildegard became a notable philosopher of the High Middle Ages. Her works span everything from morality to medicine, carefully transcribed and illuminated in manuscript form. Direct from God, these visions incorporate a concept that she uses over and over: the concept of viriditas.

Though Hildegard is not the first person to use this term (thinkers such as Augustine of Hippo, for instance, have used it before her), she really brings the concept to life in her work. Veriditas, which can be translated to “greenness,” is a theological concept that stems from God himself to humanity.

This is best depicted in her great work, Scivias, in which Hildegard details everything from moral precepts from God to biological issues such as quality of semen. The base of viriditas is the idea that God is the lifegiving force, like a tree that gives the greenness and vitality to its leaves. God’s vigor fills his creation with this sort of virility, this fecundity, or growing bounty. In our best moments, as humans, we echo that from above in our fruitfulness, or life-affirming qualities. God offers to humanity not simply life, but a flowing, beautifully tangling life force like a gently encroaching vine of a well-cared for plant.

The term is a theological one in nature, but can be seen in other lights. Human nature is, at its source, life-affirming, flowering, and vigorous when it is healthy. When out of health, we as humans do not flourish or flower. We shrivel at the vine. Thinking in terms of human healthiness that is not just a good review from the doctor during an annual checkup can make us consider what gives and maintains this overall well-being.

Thinking of viridity in terms of a whole rather than pieces of human well-being, we might consider what makes us flourish rather than simply exist. When do you feel most at one with the world? When do you feel healthiest, in more than a physical sense? Human flourishing is more than simply the ability to avoid the doctor due to decent health. It may concern self-care, the ability to create, staring into the void a little less, and the ability to give of oneself to others. If you aren’t well, you are not going to do as great a job of helping others.

I should mention here, however, that while Hildegard of Bingen is still respected from her medical texts (especially her many herbal remedies), it is important to note that she was working within a time period where the practice and theory of medicine was very different.

During this time, and well into the modern period, the main methods of medical practice relied on what is called humoral theory. This was an idea popularized in the West by Hippocrates, that everyone had four “humors,” or fluids in their body that regulated everything. When these humors are kept in balance, your health will be copacetic. However, too much (or too few) of one of these, and something would be out of whack.

The four humors included blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. An excess of black bile would make a person melancholic, or depressed, for instance. An excess in yellow bile would create a choleric, or irritable temperament. It must be noted that none of this holds water in the wake of our contemporary medicine. It’s all fascinating as theory, but not remotely based in reality.

Hildegard retained popularity as a saint in everything but name. That is, she was venerated as a saint well after she died, but was not canonized, or officially made into a saint by the Catholic Church, until 2012. During that time, Pope Benedict XVI not only recognized her as a saint, but made her a “Doctor of the Church,” an honor bestowed on a few saints whose teachings are considered essential.

During the late 20th century, however, Hildegard received recognition in other circles. The New Age movement embraced her writings on natural healing in their own practices. Her music was also performed and recorded extensively, by church and non-church folk alike.(Don’t believe me? Look her up on Spotify or YouTube, and check out Hildegard von Blingin’ while you’re at it.) I mean, when you release bangers like an opera about a face off with personified vices, you’re kind of a big deal.

What keeps Hildegard of Bingen in the popular imagination isn’t just her sweet, sweet jams or her prescient medical knowledge that did, in many respects, transcend that of the time. It may not even be her saint cred. It is, I think, in part because of her ability to undermine every medieval stereotype we consistently maintain in our popular knowledge base.

One of my first experiences in college as an undergrad involved going to a faculty symposium, where professors from multiple disciplines spoke specifically about this 12th century nun. I remember listening to two of my (later favorite) professors speak on her art and philosophy. For someone who had considered religious life before I converted to Catholicism later as an adult, it was amazing to see a religious woman so multi-talented and powerful.

For years, I considered convent life–or at least life in a religious order. The idea of living in a community and serving in tangible ways held incredible appeal to me. It was a dream that my heart wished to pursue until recent years, a dream that began when I saw “Sister Act” at an age that was probably inappropriate.

Viriditas is a powerful way of thinking about things. I thought for so long of being an educated teaching nun, and that this was where I would flourish. Sometimes, I think, there are multiple paths to creating and maintaining a flourishing, flowering life, just like a good plant has many different vines and leaves. We can, perhaps, consider in what ways we are currently flourishing as a whole, where we can improve this, and strive to plant the green seeds of viriditas in others through our actions.

As a side note, the famous neurologist Oliver Sacks wrote a book of case studies of complex neurological issues, which included a chapter about Hildegard of Bingen and her visions. In The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Sacks details the physiological effects of her visions, ascribing them to very specific kinds of migraines.

A kind and conscientious writer, Sacks speaks of Hildegard’s visions with surgical precision, but also takes the time to say that, even if physiological in nature, this does not demean or decrease the impact of her experiences and their religiosity. Perhaps he was thinking in terms of viriditas, how we flourish, just like Hildegard.

The existence of prominent mystics such as Hildegard of Bingen during the Middle Ages undermines stereotypes we have about the period.

Hildegard of Bingen was a multitalented polymath who excelled in theology, art, music, and philosophy, writing the first opera.

Hildegard's concept of veriditas gives us a more holistic approach in terms of health and well-being, the idea that we can (and should) flourish.

While theological in nature, veriditas can be viewed in light of what makes us sprout, flourish, and flower as human beings.

Hildegard of Bingen continues to influence us in our contemporary age, though music, art, and medical texts.

You liked this blog post and don't want to miss any new articles? Receive a weekly update with the best philosophy memes on the internet for free and directly by email. On top of that, you will receive a 10% discount voucher for your first order.

Your cart is currently empty.