Marx vs. Nietzsche: The Misunderstood Philosophy of 'Religion is the Opium of the People' and 'God is Dead'

|

|

Time to read 7 min

|

|

Time to read 7 min

What did Karl Marx actually mean when he wrote "religion is the opium of the people"?

How has Nietzsche's famous "God is dead" proclamation been misinterpreted by both atheists and theists?

Why is understanding philosophical quotes in their full historical context essential for proper interpretation?

When we are teenagers of a certain age, we tend to fall into two philosophical camps: the revolutionary, capitalism-smashing Marx crowd or the woe-is-me-but-I-am-special, Übermensch-y Nietzsche crowd. Both (along with a few others) are beloved of the young, hormonal and coming of age crowd.

Two of the most famous facial haired edgelords of philosophy, Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche are both well known for their anti-religious stances over the course of their work. Marx is often quoted as dismissively writing that “religion is the opiate of the masses,” while Nietzsche is purported to proclaim, “God is dead.”

What do the revolutionary and the professional grumpypants really have to say in these deliciously atheistic attacks on religion? Are they really as hardline as everyone who posts their words (as memes, of course) on social media wants you to believe?

The oft-googled quote by Karl Marx is used both by aggressive atheists in their attempts to share with others their newfound knowledge that religion sucks and is not a real thing, and conservative reactionaries who use it to prove that Karl Marx was mean about religion and therefore that is why he is not nice to capitalism. It turns out that neither your newly atheistic friend nor your Ayn Rand adoring friend are correct in this case. (Who knew.)

When using this paraphrase (not the actual quote), both sides like to emphasize the word “opiate” and the word “masses.” By using the word “opiate,” they argue, our boy Karl insists that the practice of religion is illicit, just like opiate drugs (like opium itself). We think sometimes of someone like poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge , for instance, slowly wasting away and having weird visions of Kubla Khan .

For the atheist side, this is seen as some shade thrown at religion, because you are just using it as another way to get high and lose touch of reality. For those on the religious side, the concern is that you can’t equate traditional religion with hallucinative substances, and that it is not a smart argument to make, being kind of sophistic in nature.

Where did people get this quotation, though? Like things that are often disseminated online (and even before social media!), the quote was taken out of the context of its greater text. Surely this mega angsty quotation came straight out of the Manifesto, no? Nope.

Our anti-religious rant came from one of Marx’s earlier, unfinished works, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy (1844). That’s right, Hegel fanboy Marx wrote about Hegel. The quote within this text goes like this:

Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

As suggested by David Papke (Professor of Law at Marquette University), it is important to take the word “opium” in its contemporary-to-Marx context. Opiates during the nineteenth century, while seen as something that someone could abuse (in the case of Coleridge’s opium or laudanum abuse by Victorians), it was more commonly seen as a medicine, just like medications we take today can be abused but are not seen as illicit. Papke notes also that this was not something illicit during that time period.

Keeping this in mind, let’s better unpack the quotation. If religion is the “heart of a heartless world” and “soul of soulless conditions,” and it it is something like a medicine to humans, then perhaps Marx, while not in love with it himself, can see its utility and purpose for people who are constantly exploited and demeaned by their fellow human beings.

Just like with medications, religion can be a healing balm to those suffering, but can also be used to mask the underlying reasons for the suffering, like throwing a bandaid on a gaping wound. However, sometimes we need the bandaid to keep functioning.

Perhaps it is not as aggressively atheistic as both sides would like us to believe.

But what about Nietzsche? Come on! Surely this guy is full of black emo blood and misery? People like to churn out meme after meme with the “God is dead” quote, the firm atheists just pointing to it after posting it with a knowing nod, and the theists rolling their eyes and writing apologetics about God not being dead because Nietzsche is intellectually lazy and silly.

But surely the quote can just stand by itself, amirite? It’s there. It’s loud. It’s pretty freaking proud. Unlike with Marx you can’t really spin that, right? Right??? Well, actually…

So here’s the thing about Nietzsche’s precursor to a Nine Inch Nails song . It first appears in The Gay Science (1882), then it appears in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883) multiple times. The phrase is best explained in a passage from the former work:

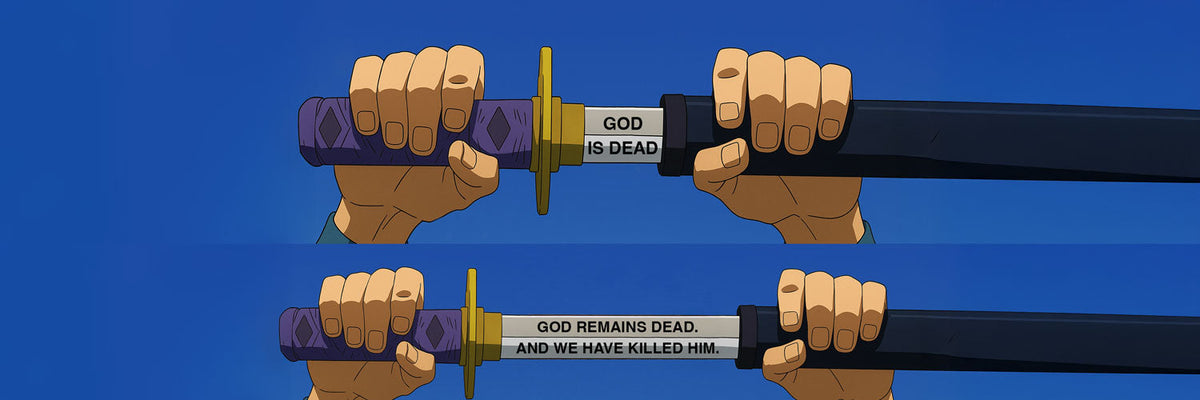

“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was the holiest and mightiest of all the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood of us? … Must we ourselves become gods simply to appear worthy of it? There has never been a greater deed: and whoever is born after us–for the sake of this deed he will belong to a higher history hitherto.”

In The Gay Science, these words are spoken by a madman, a character who becomes the mouthpiece for some of the more controversial of Nietzsche’s ideas, including this one, produced in a period of history where religion and belief in God were considered a matter of fact.

But the madman, a sort of prophet who later speaks through Zarathustra, the eponymous character of Nietzsche’s later work, is perhaps more lucid in his words than we give him credit for–or rather, lucidity is not the point altogether. Nietzsche, in much of his work, takes common assumptions and flips them on their head in a very playful way (hence the title The Gay Science, indicating an almost cheerful playfulness).

So when Zarathustra gets to repeat this phrase in an almost religious fervor: “God is dead: of his pity for man hath God died,” there is a blasphemous part to it, sure, but also some trollishness.

And while Nietzsche is firm in saying God is dead, he doesn’t say that this deicide comes without consequences. Just like Lady Macbeth in Shakespeare’s Scottish play, when we commit the crime of murder, we have to contend with the (not always pleasant) consequences of the act. When we kill God, even if we supplant him, we have the blood on our hands and lose many of our psychological comforts.

And this is why it takes a madman to make this proclamation.

Philosophy can be incredibly powerful, setting up foundations for whole systems of thought. When we engage with it, we engage in a conversation, not only with that philosopher's thoughts, but also with those of the entirety of the history of thought. Incredibly, thinkers like Marx and Nietzsche can remain relevant over a century after their deaths. Powerful ideas have a tendency to retain their bite.

However, the mistake we have a tendency to make, especially when we begin engaging with philosophy, is in taking the words of our favorite (or least favorite) philosophers out of context, or first encountering them that way. In short, if you find an intriguing soundbite, it helps to dig in rather than accept it as an undisputed fact.

What makes philosophy so unique is that we are encouraged to dig and dig, to let our curiosity change us into the critical thinkers and questioners of the world. So, next time you see a cool quote, find out where it came from. You may be surprised and you may find out something far more interesting than you first thought!

The famous quotes from Marx and Nietzsche about religion are frequently taken out of context and misunderstood

Marx's full quote about religion includes seeing it as "the heart of a heartless world" and should be understood with 19th-century context of opium as medicine

Nietzsche's "God is dead" proclamation comes from a character called the madman and addresses the consequences of abandoning religious belief

Both philosophers had more nuanced views on religion than their commonly quoted soundbites suggest

Understanding philosophy requires engaging with the full context rather than relying on isolated quotes or memes

You liked this blog post and don't want to miss any new articles? Receive a weekly update with the best philosophy memes on the internet for free and directly by email. On top of that, you will receive a 10% discount voucher for your first order.

Your cart is currently empty.