Epicurus Unchained: A Defense Against Dante's Condemnation

|

|

Time to read 7 min

|

|

Time to read 7 min

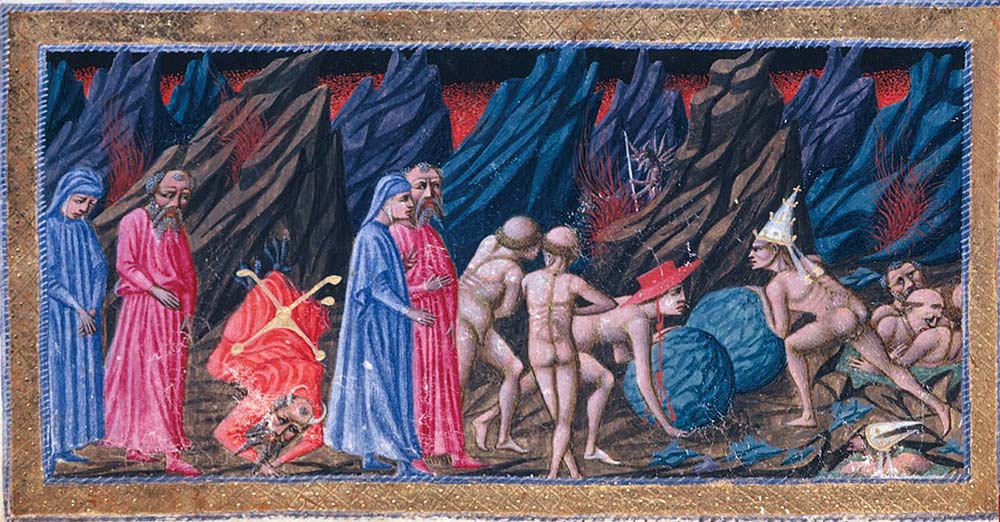

Dante's Inferno - Circle 4 - Canto 7: The avaricious, the greedy and the profligate; Priamo della Quercia, 15th century.

How did Dante's view of Epicurus reflect the medieval Christian rejection of materialist philosophy?

Why might the suppression of Epicurean thought have delayed scientific and medical progress for centuries?

What lasting impact did Plato and Paul have on Western philosophical and religious thinking about body and soul?

Dante's Inferno - Canto X, 13-15

Banished to the dark sixth circle of hell, Dante placed Epicurus and all his followers. Their sin? "On this side lies the tomb of Epicurus with his whole school, who hold that the soul dies with the body."

Dante, deeply rooted in the notions of the Christian Middle Ages, follows a ban that was pronounced by the end of late antiquity. To doubt the dualism of body and soul would mean to contest the valid truth of Christian doctrine. Now, as a great lover of the pluralistic thinking of antiquity, I, hardly a philosophical layman in terms of my knowledge, would not like to fall into the same tenor as Dante.

I do not intend to condemn the Christian doctrine of the High Middle Ages, nor would I be able to do so. A fair understanding of Dante's conceptual world requires the most comprehensive knowledge of his time. With a wink, I distance myself from serious, truth-committed dogmatics and allow myself to grant Epicurus and antiquity a resurrection in a humorous way, or rather to climb out of the open coffin in the sixth circle of hell.

In the sense of Dante's accusation, I, as Advocatus Diaboli alias Epicuri, declare the accused: NOT GUILTY. With the lance of rebirth - sic: Renaissance - and the shield of humor, I redeem Epicurus from evil. My standard-bearer in this humane crusade against a prickly, conservative sentiment, not thinking, is a Roman poet who is unfortunately largely unknown today.

The name Lucretius is familiar to the educated bourgeoisie, but his book "De Rerum Natura" may today be presumed to be in a - firmly closed - coffin. Make a book out of the coffin: put a lid on it, the most effective form of book burning.

Not an easy book to read, in the original it presents even good Latinists with the highest hurdles, for me with far too high hurdles. Lucretius is a poet, and in poetic language he wrote a textbook on "physics." A brief digression: "Nature" is a term used as frequently as it is rarely precisely questioned. Here I aim at an understanding in terms of natural science.

Lucretius describes phenomena such as thunder and lightning, ponders natural forces, and thus follows the atomistic world view, which, formulated before Epicurus, anchors the reason for all manifestations in the world in material smallest building blocks, elements we would say today. World in the sense of the Greek cosmos, which in the most comprehensive sense would be translated today in popular science as universe. It is simply impossible not to think in Christian terms with these terms. Everything revolves - vertit - around the One - uni - This original unum is, according to scholastic high medieval doctrine, as God essentially dissimilar to all other res arising from it.

For Epicurus, exactly the opposite is true. All manifestations of the universe are essentially the same as bodies formed by atoms. Stardust, broom, ant, and Christian ascetic all have a common origin. They have emerged from a matter and will pass into other forms of matter as matter.

The most decided opponent of Epicurus is, in terms of content, Plato. He answers the unpleasant question of inconstancy or transience - Heraclitus' pantheism consistently negates the concept of a constant being, everything is in constant becoming, decay - through a verdict of faith that remains valid for many to this day: the body is a prison for the soul.

According to Plato, the soul is exempted from Heraclitus' pantheism; it does not dissolve but is eternal. But as a consistent dictator, Plato does not leave it at a general immortality of the soul, but adds special supplements. Depending on one's way of life, a rebirth will take place in a new body prison, in the best case as a new Plato alias male philosopher - Plato's three-estate doctrine - otherwise as an ant, broom, or in the worst case as a woman. Please smile again; this nonsense has been preached by cultures, religions, and "great" philosophers up to the present day: Even today, many women and men cannot imagine female popes. With Plato, the doctrine of being connects with morality. As you live, so you will be reborn or, according to Dante, so you will simmer in hell or jubilate in paradise.

Now a daring, much too big leap, due to the brevity of space. Antiquity knew, roughly speaking, no revealed truth; the plurality of gods allowed even an atheist like Lucretius to live. Dogma as a truth of faith is not a property of antiquity; despite Plato's claim to universal validity, there remained a most cheerful space for cheeky mockers like the Syrian Lucian, who made fun of the clever philosophers and sublime deities of antiquity in the most cheerful way.

This cheerful, open attitude, arising from the most tolerant thought of antiquity - I know that I know nothing / scio me nihil scire - came to an end when the proclaimed truth made its entrance.

The successors of the stonemason from Athens (Socrates) did not stay true to his trade. Nietzsche's great aversion is, unmistakably, to Luther, who as a reformer led for him not into modernity but back into the Middle Ages. In other words, Nietzsche in his thinking turns the Platonic dialogues around and speaks from the perspective of another group of philosophers maligned to this day: the Sophists. Their greatest crime was not the denial of the soul, no, it was the denial of an objective truth.

The Homo-Mensura thesis of Protagoras is all too often misunderstood as a claim to power by humanity, whereas it emphasizes the powerlessness of humans to know more than a subjective truth. "Man is the measure of all things. Of those that are, that/how they are, of those that are not, that/how they are not."

Request to faint and remain modest in this state.

Luther, in turn, became great and famous as a student of Augustine and Paul. Paul now has said the most essential things about Christianity in his letters to the emerging communities of Christianity and has thereby shaped it down to the smallest crevices. To put it pointedly, Christians are much more Paulians. And Paul passes on a Platonic world view in his "mails" to the emerging Christian communities.

Imagine the emails of a conspiracy theorist who, in the face of an impending climate catastrophe, demands to renounce the internet, showering, blow-drying hair, and extramarital sex, would become state religion in 400 years as holy revelations of God, then you - as a user of the internet (you are currently reading online, possibly showered and blow-dried, and dreaming forbidden dreams) - would logically be condemned to sleep in open coffins for disregarding divine truths.

Please smile kindly: I have been polemical here and have laid it on rather thick. But the final question may be permitted. If Epicurus had not experienced hell's damnation and if his worldview had become a widespread alternative, then the ancient technology, which was at an astonishing level, would not have experienced an upswing only from the Renaissance onwards, but would have allowed ways for progressive medicine - dealing with body and soul as a unity - much earlier, as Islam did in Andalusia and Baghdad.

Should you now shake your head and have found all this too confusing, then read Lucretius' "De rerum natura" - or, more simply, Steven Greenblatt's "The Swerve." This book vividly explains the significance of the rediscovery of Lucretius and thus of Epicurus' teaching for the emergence of modern thinking. Or you retreat with the cheekiest philosopher of antiquity, the Cynic Diogenes, into a barrel for a refreshing siesta. This barrel was, of course, an expression of the contempt for death of the punks of the time, the Cynics: an open coffin.

You liked this blog post and don't want to miss any new articles? Receive a weekly update with the best philosophy memes on the internet for free and directly by email. On top of that, you will receive a 10% discount voucher for your first order.

Your cart is currently empty.