The Birth of Nietzsche from the Spirit of Philosophy

|

|

Time to read 13 min

|

|

Time to read 13 min

Who was Friedrich Nietzsche and why is he a big name in philosophy?

What can Nietzsche's ideas of aesthetics teach us about the nature of beauty and art?

Why are Friedrich Nietzsche and his work still relevant today?

Friedrich Nietzsche, an October baby, was born in 1844 in Prussia, or what we would call Germany today. A well-educated and intelligent scholar, Nietzsche attended university at the University of Bonn, and when ending his studies, he became the youngest professor at the University of Basel, in Switzerland, at 24.

His academic career was short-lived due to chronic bad health. Constant headaches plagued him, as well as an injury from his time as a cavalry soldier. Having studied as a philologist, or language expert, Nietzsche soon moved on to philosophy, and this is where it gets interesting.

Since his academic career was curtailed by bad health, Nietzsche took up his writing career in earnest. Early on, he was a fanboy of the highly controversial composer Richard Wagner, the one of the Nibelungenlied (Ring Cycle) fame. Wagner thought Nietzsche was pretty silly, even though the philosopher wrote some music himself. Out of love for his icon, Nietzsche wrote The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (1872), a love letter to Wagner, but a formidable piece on aesthetics.

Traveling in the same circles, Nietzsche met the alluring Lou Salomé, a highly intelligent and capable woman for whom he fell head over heels. So captivated by her was Nietzsche that he proposed to her twice (or, according to Salomé, three times . Probably rolling her eyes, Lou Salomé rejected him, hard. Dejected, Nietzsche wandered off, his work becoming more and more polemical in nature.

He produced iconic texts such as The Genealogy of Morals (1887), Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-5), Twilight of the Idols (1888), and other texts that are essential to the philosophical conversation today. His work is known for its readability, and its poetic nature. For some, this can make his oeuvre difficult to read, but others find this a selling point. In reading Nietzsche, I can assure you of one thing: you will never, ever be bored.

In philosophy, aesthetics is the study of beauty. Usually, this subject tends toward visual art, but, to quote Madonna, “Beauty’s where you find it.” In aesthetics, we ask the questions: What is beauty? What makes something beautiful? Why is it beautiful? Why does it elicit an emotional response from us?

In The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (henceforth known as Birth of Tragedy), Friedrich Nietzsche talks about the very nature of art itself, and speaks through the lens of historical context. He creates a genealogy of sorts.

As aforementioned, the Birth of Tragedy was written when Nietzsche was a fanboy of Wagner, a composer known for his (melo)dramatic operas, who was doing some stuff that people really loved back then, and much later. Indeed, in the 20th century, he had another famous fanboy who was gross (Hitler).

And we will come back to this, but for now, keep in mind that part of this is his bromance letter to Wagner, but that it also doesn’t take away from Nietzsche’s finer points on aesthetics, separate from Wagner and his bandwagon.

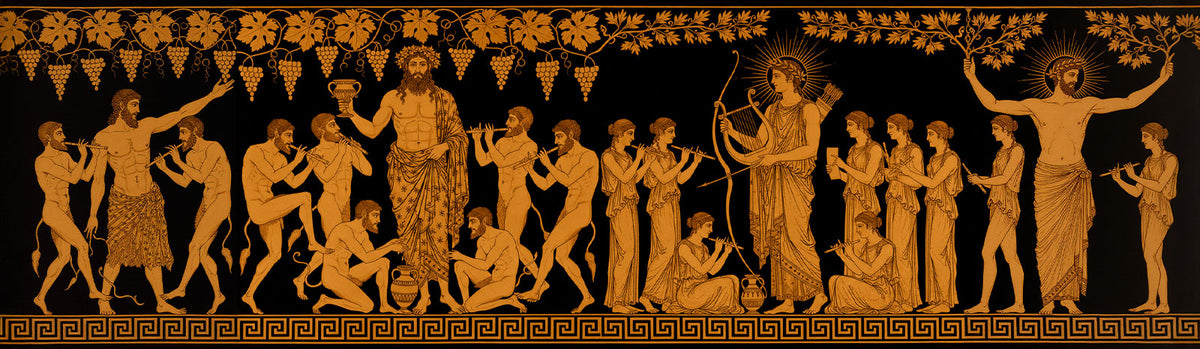

In Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche wants to explain how tragedy (one of the finest peaks in human artistry) comes to be, and why it is just so good. In doing so, he explains that, in the Ancient Greek world, two forms of music and drama existed: the Apollonian and Dionysiac.

So, let’s take a trip to Ancient Greece. Imagine, if you will, an amphitheater. When I say this, I do not mean to imagine that you’re going to see Nine Inch Nails live (though that would be cool). The OG amphitheatre looks like a grassy stage with a bunch of stone benches in a semicircle around it. No awesome lighting or plugged in guitars. Or guitars at all.

But what it is good for is allowing for a play to happen, and for some good vocal projection when awesome acoustics were not really a thing. Imagine, further, that you’ve got a play going on. But this play involves people wearing masks. And you’ve got a chorus. No, not some robed people in the back singing from sheet music. People in the background who are singing help illustrate the point of the play going on. They may sing harmoniously, or they may cry out.

And Ancient Greece did love it some plays. You have playwrights from Aristophanes (writer of the bawdy Lysistrata) to Sophocles (who penned the original “your mom” play, Oedipus Rex). And each playwright and play had different ways of going about things.

According to Nietzsche, these ways of going about things in Ancient Greece could be sorted into two approaches: the Apollonian and the Dionysian. These are the two factors that join together to give birth to tragedy.

The first of the approaches to art is the Apollonian. This approach is named after the god Apollo, who is the dude who rides his chariot through the sky to drive the sun around through the day. Apollo is known for his logic and his very rational beauty. Apollo can be found in the proportional consistency of a Greek statue, for instance.

And Apollo is often found in the visual arts, because of the precision often required to get good at painting or sculpting. And it’s true, if you think about it. When you train as a visual artist, you often start off with learning rules. Perspective, light and darkness, proportionality. You want something to look realistic at first. This is the starting off point for many artists, and what you will likely get at art school.

Apollo, a beautiful and hot (in more than one way . . . sun god joke, ahem) god, is one of the most predictable of the Greek gods, if you think about it. He rises and sets every day, around the same time. And so his representation of a more rational approach makes sense.

And when Nietzsche was writing, in the 19th century, this rational approach would have been the majority of visual art at the time. In 1872, Impressionism, the movement later popularized by people like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, would not have kicked off in earnest yet. Most of their works were currently getting rejected.

During the mid-19th century, realism was in full swing. You’ve got artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and Gustave Corbet making some very photo-realistic stuff. And you have a return, in a lot of respects, to the Greeks, with Greek revival sculpture being the joy of the French Academy, and a return to the more realistic paintings of Raphael by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In this sense, there is an observation of the world around one, and an attempt to produce it in a rational, sensible way, that is appealing in its likeness to our observed reality.

Juxtaposed to the Apollonian is the Dionysian as another approach to art. This approach is named after the god Dionysus, the chonker who rides around in his own chariot, along with his posse of drunk and orgiastic friends. He is a god of levity, of excess, of wine. And of madness, in his own way.

Friendly yet dangerous, Dionysus is known for his satyr attendants, lustful little goat-men, and also for his (usually female) followers who work themselves into a frenzy. Dancing like mad, they get themselves into an altered state and rage and ravage. While it might be sexy to be part of a drunken orgy, it is also hazardous.

For Nietzsche, the Dionysian approach to art is most often found in music. The primal beating of a drum, the shrieks of a singer, the emotional pull of a love song. All of these come from a part of human experience that is irrational and emotional. And this is where Dionysus diverges from Apollo.

And it’s relatable. Whether you are listening to Taylor Swift sigh over an ex or your favorite metal band scream into the void (very Nietzschean), the emotion is there, the certain something that feels if only just a little irrational in nature. And it’s true, because part of music’s job is to evoke emotion. Even something as rational sounding as Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (AKA A Little Night Music, AKA the one everyone knows) can provoke feelings of whimsy, for instance.

And this approach is what those people in the Greek chorus are taking, rending their garments and screaming at the audience to illustrate the well-written (and, in a lot of respects Apollonian) words of the playwright.

And Nietzsche brings it home for us. When we add these two approaches together, we get the finest form of art: tragedy. Let’s head back to the Greek amphitheatre, then.

The tragedy uses the rational from the Apollonian and the irrational from the Dionysian. While Oedipus is written with an Apollonian precision, it is written in such a way as to evoke emotions of horror, disgust, sadness, and anger, among others. With the Dionysian, it takes things back to a primitive place, where emotions become central to the experience.

While the Apollonian and Dionysian tendencies in art grew apart for so long, Nietzsche argues, when combined, they create, in works such as Wagner’s operas, an aesthetic height of achievement. It is in tragedy that we learn so much about human experience and what it is like to be human. We see shards that reflect ourselves, as both rational and irrational beings.

Consider, for example, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in which the protagonist, never very happy to start, vacillates about his choices for quite a while before the incredibly tragic end. In the titular character we can see certain parts of the human condition that may not always make sense, but that evoke an emotional response, whether that response be, “Will that annoying guy stop whinging?” or “You know? I get that.”

And this is where aesthetics are important. They do not have to directly teach something, in the sense that not everyone needs a blatant moral to the story. They do not have to fit a certain mold. I sometimes wonder what Nietzsche would have thought about the work of Edvard Munch, for instance. But good aesthetics reflect something about ourselves or the world around us in a way that impacts our lives and way of being.

Even someone like Oscar Wilde, who would proclaim “art for art’s sake” to the world in the majority of his work, has something to teach us about the use and purpose of ornamentation, about the reason to accept beauty in the world. “Beauty’s where you find it,” to reiterate philosopher Madonna’s words.

Nietzsche soon fell out with Wagner, his bro for a very hot minute. After the thing with Lou Salomé, which was complicated by the machinations of his sister, he retreated into solitude, his health problems, including deteriorating vision and what some have suggested might be syphilis, plaguing him.

Nietzsche was institutionalized after a breakdown. The breakdown, by legend in part the result of seeing a horse being abused in a street and running to its aid, put him into a hospital, and then into the arms of his sister. He wrote letters that didn’t make too much sense to his friends, his work no longer doable. The syphilis theory makes sense here, as the illness may have progressed to neurosyphilis, spiraling into an intense mental health problem that would only get worse.

His sister, a controlling and religious person who had married a career antisemite and tried to start a German colony of like-minded people in Paraguay. It didn’t work out so well. However, as his living relative, she was able to take him to her house and “take care” of him as he descended into a deeper and more concerning mental spiral.

During his descent, his “enterprising” sister decided to do two things. First, she decided to edit his works, the ones she was never too fond of or interested in, as they looked lucrative. Second, she let people in to see a man who really, really wasn’t doing well, creating a kind of sideshow environment for someone who was wasting away.

After two strokes and contracting pneumonia, Friedrich Nietzsche passed away in 1900 at the age of 55. Ardently opposed to antisemitism throughout his life, Nietzsche would unfortunately gain a following among such people.

For you see, his enterprising sister decided to add in some hate here and some hate there into his works, so that he could look like another pseudo-intellectual of the time period. And for a long time, it was difficult to remove these nasty little sprinkles from the original texts, given that she controlled his legacy.

For Nietzsche, the antisemites were just as bad as the religious people he condemned. There are many letters written that indicate this disdain he felt, and it is one of a few very complicated reasons why Nietzsche broke with his idol Wagner and ended up throwing a lot of shade in the way of that composer.

And indeed, the antisemitism of Wagner, as well as his nationalism are the two biggest draws for his very prominent and nasty fanboy, Adolf Hitler. It should be noted that this abhorrent way of thinking about Jewish people had become quite common at the time among many German people. Similar to the “scientific” ways people tried to “rationalize” white supremacy over people of African descent, and therefore make slavery acceptable, these “intellectuals” had reasoned that Jewish people were, somehow, why they had issues.

It’s similar to the little incel TikToker claiming that women are the problem why he, a single man, can’t get a date. But hopefully this TikToker isn’t going to start a genocide or enslave people.

Friedrich Nietzsche was a human being, just like the rest of us. He had a more incredible moustache than most, admittedly, but he suffered from chronic illness, had spats with friends, got rejected by women, and lived a complicated life. He wrote some of the most incredible works in philosophy, whether you agree with him or not. And he is simply hard to pin down, because he was himself, and not a mouthpiece for someone else or for someone else’s movement.

I find Nietzsche to be deliciously complicated. When I first read Thus Spake Zarathustra(the Kaufmann translation, still a gold standard in my opinion), I found him annoying. Later, I would characterize him as the OG incel. But that is unfair to him.

Returning to Nietzsche for my first published journal article, on the band The Cure and melancholy, I began to understand that, while I read Nietzsche extensively almost 20 years ago, there were aspects to him that I simply did not understand or grasp. It can be easy to get stuck behind the “God is dead” cutesy quote, and box Nietzsche easily. But you can’t.

Nietzsche writes like no one else in philosophy. While the French existentialists and British/American analytics adore their jargon, Nietzsche writes poetry. While Kant writes in a way that is so explanatory that you just get lost, Nietzsche writes in a way that evokes emotion, yet uses images that are evocative and easy to understand.

In another blog article, we joked about Nietzsche being in the starter pack for young teenage boys. We laugh about it, but Nietzsche is a good starter philosopher because he is readable. His writing is art and accessible to those even outside of philosophy. And that makes him unique.

In addition, as someone who suffers from chronic illness, I can relate to the difficulty of writing while being severely ill. That makes him human, all too human.

So, happy (belated) birthday, Friedrich! Thank you for your work over which we can argue (and be pretentious) for hours. And thank you for your unique perspectives.

Friedrich Nietzsche was a philosopher with a complicated biography and complicated ideas.

Nietzsche wrote The Birth of Tragedy to explain how two modes of artistic beauty come together to create tragedy, the pinnacle of aesthetics.

The two forms of art are the Apollonian and Dionysian, named after two ancient Greek gods.

The Apollonian represents rational beauty, while the Dionysian represents emotional beauty.

Nietzsche's work, while divisive to this day, is still compelling and relevant.

You liked this blog post and don't want to miss any new articles? Receive a weekly update with the best philosophy memes on the internet for free and directly by email. On top of that, you will receive a 10% discount voucher for your first order.

Your cart is currently empty.