Hypatia of Alexandria: The Brilliant Mathematician Who Defied an Empire

|

|

Time to read 13 min

|

|

Time to read 13 min

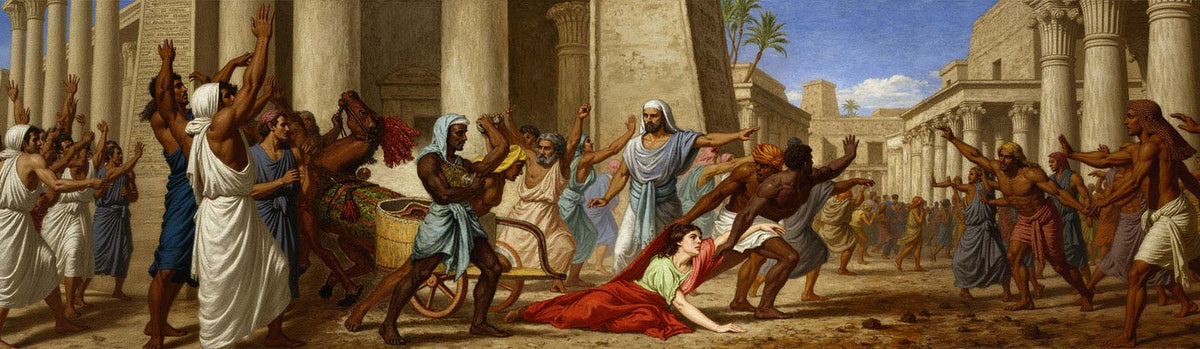

“Death of the philosopher Hypatia in Alexandria,” stylized version, originally by Louis Figuier, first published in 1866. Yes, we know she probably wasn't that white.

Who was Hypatia of Alexandria and how did she become the ancient world's most respected female mathematician and philosopher?

What groundbreaking scientific contributions did Hypatia make to mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy in the 4th century?

Why was Hypatia murdered and what does her tragic death reveal about the clash between science and religious extremism?

In the year 415 CE, a mob dragged one of history's greatest minds through the streets of Alexandria and murdered her in brutal fashion. Her crime? Being too intelligent, too influential, and too unafraid to speak truth in an age when powerful men demanded silence from women.

Hypatia of Alexandria wasn't just remarkable for a woman of her time. She was remarkable, period. While most people in the 4th and 5th centuries struggled with basic literacy, Hypatia was solving complex mathematical equations, improving astronomical instruments, and teaching philosophy to the Roman Empire's intellectual elite. Her lecture hall was standing room only, filled with students who traveled from across the Mediterranean to study with her.

She lived in an era when women were expected to be silent, obedient, and confined to domestic life. Instead, Hypatia became the head of Alexandria's prestigious Neoplatonic school, advised government officials, and commanded respect that most men of her time could only dream of achieving. Her story is both inspiring and tragic, revealing what one woman could accomplish against impossible odds and what forces arrayed themselves against female brilliance.

To understand Hypatia's achievements, you need to understand Alexandria in the 4th century CE. This wasn't just any city. It was the intellectual capital of the ancient world, home to the famous Library of Alexandria (or what remained of it) and the Mouseion, an ancient research institute that would make modern universities jealous.

Alexandria sat at the crossroads of Greek, Egyptian, and Eastern cultures, creating a unique environment where ideas from different traditions mixed and evolved. Scholars debated everything from the nature of the cosmos to the foundations of ethics. Mathematicians built on the work of Euclid, who had lived and worked in Alexandria centuries earlier. Astronomers mapped the heavens with increasingly sophisticated instruments.

Into this vibrant intellectual scene came Hypatia, born around 360 CE. Her father, Theon of Alexandria, was himself a distinguished mathematician and philosopher who taught at the Mouseion. Unlike virtually every other father of his era, Theon decided his daughter deserved the same rigorous education as any son. He personally oversaw her training in mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy.

This decision was revolutionary. Women in the Roman Empire could sometimes receive basic education, but advanced study in mathematics and philosophy was considered not just unnecessary but potentially dangerous for women. The prevailing attitude held that women's minds were too weak for abstract thought and that education might make them rebellious or unfeminine.

Theon apparently didn't care about these attitudes. He recognized his daughter's exceptional intellect and refused to let societal prejudice waste it.

By her thirties, Hypatia had surpassed her father's achievements and become Alexandria's leading intellectual figure. She headed the Neoplatonic school, a position of enormous prestige that put her in charge of teaching the city's brightest students about philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy.

Her teaching style was apparently magnetic. Historical accounts describe students packing her lectures, hanging on every word as she explained complex mathematical proofs or guided them through Platonic philosophy. She didn't just recite established knowledge; she challenged her students to think critically, question assumptions, and develop their own understanding.

What made this even more remarkable was that she taught in public. In an era when respectable women were expected to remain largely secluded, Hypatia walked through Alexandria's streets in the distinctive robes of a philosopher, engaged men in public debate, and lectured to mixed audiences. Contemporary sources suggest she remained celibate throughout her life, possibly understanding that marriage would have compromised her independence and authority.

Her reputation spread far beyond Alexandria. Students came from across the Roman Empire to study with her. Many of her students went on to become bishops, government officials, and influential scholars themselves. They wrote about her with reverence, describing not just her intellect but her character, noting her fairness, her patience with struggling students, and her unwavering commitment to rational inquiry.

Hypatia's scientific contributions are frustratingly difficult to pin down with precision because none of her original works survived. What we know comes from references in other scholars' writings and letters from her students. But even this fragmentary evidence reveals someone operating at the highest levels of mathematical and astronomical research in her time.

Her most significant mathematical work was a commentary on Diophantus's "Arithmetica," a thirteen-book treatise on solving algebraic equations. Diophantus is sometimes called the "father of algebra," and his work dealt with what we now call Diophantine equations, problems where you're looking for integer or rational solutions. Hypatia's commentary didn't just explain his work. She clarified difficult passages, corrected errors, and apparently extended some of his methods. Her student Synesius specifically mentions her work on this text, and later Arabic mathematicians who preserved Greek learning referenced a commentary on Diophantus that scholars believe was hers.

She also wrote a commentary on Apollonius of Perga's "Conics," an eight-book study of conic sections (parabolas, hyperbolas, ellipses, and circles). This was hardcore geometry, the kind that required sophisticated spatial reasoning and rigorous proof techniques. Conic sections weren't just theoretical curiosities. They had practical applications in optics, astronomy, and architecture. Understanding Apollonius well enough to write a useful commentary meant Hypatia was working at the frontier of geometric knowledge.

In astronomy, Hypatia collaborated with her father Theon to produce an improved edition of Ptolemy's "Almagest" and his "Handy Tables." The Almagest was the standard astronomical reference work, explaining the geocentric model of the universe and providing methods for calculating planetary positions. The Handy Tables simplified these calculations for practical use. Revising these works required not just understanding complex mathematical astronomy but also making observational checks and judgments about which of Ptolemy's methods and numbers needed correction.

Several sources credit Hypatia with work on astronomical instruments. The most specific claim comes from Synesius, who describes an instrument she helped him construct that sounds like an astrolabe. An astrolabe is a sophisticated device that models the celestial sphere and can be used to solve problems involving time, the positions of stars and planets, and latitude. Building one requires understanding spherical geometry, astronomical theory, and precision metalworking. Synesius also mentions a "hydroscope" (likely a hydrometer for measuring liquid density) that Hypatia helped design, suggesting she had practical interests beyond pure mathematics.

Her philosophical teaching focused on Neoplatonism, particularly the works of Plotinus and his student Porphyry. Neoplatonism wasn't just abstract metaphysics. It was a comprehensive worldview that explained how reality was structured, how knowledge was possible, and how humans should live. Hypatia's approach apparently emphasized the connections between mathematical reasoning and philosophical insight. For Neoplatonists, mathematics revealed eternal truths about reality's structure, making it a path toward understanding the divine.

What made Hypatia exceptional wasn't just that she understood these complex topics. She synthesized them into a coherent educational program and taught it effectively enough that her students became influential scholars and leaders themselves. Several of her students went on to become bishops, and their letters reveal someone who didn't just transmit information but taught people how to think critically and systematically.

Hypatia's murder in 415 CE was a calculated act of femicide, the killing of a woman specifically because she was a woman who refused to conform to expected gender roles. To understand what happened, you need to grasp the religious and political tensions consuming Alexandria at that time.

The Roman Empire had made Christianity its official religion just decades earlier. In Alexandria, this transition was violent. The city had been a center of Greek learning and religious diversity for seven centuries. Now Christian leaders wanted to eliminate pagan practices and the philosophical schools associated with them. The situation was further complicated by the fact that many educated elites, even Christian ones, still valued traditional Greek philosophy and science.

A power struggle was playing out between Orestes, the Roman prefect (essentially the governor) of Alexandria, and Cyril, the city's Christian patriarch. Orestes was Christian but believed in religious tolerance and valued traditional learning. He consulted regularly with Hypatia on philosophical matters and questions of governance. Their relationship was professional and intellectual, but in a society where women were supposed to be invisible in public life, even this was provocative.

Cyril had different priorities. He was determined to assert Christian authority over every aspect of Alexandrian life. He expelled the city's Jewish population. He challenged civil authorities. He maintained what amounted to a private militia, the Parabalani, nominally a group meant to care for the sick but functionally serving as enforcers of church power.

Cyril's supporters began spreading rumors about Hypatia. They claimed she was a witch using mathematics and astronomy for occult purposes. They said she had bewitched Orestes and was preventing reconciliation between the prefect and the patriarch through magical means. These accusations were absurd. Hypatia's influence came from her intellect and the respect she had earned through decades of scholarship. But in an atmosphere of religious hysteria, rational explanations didn't matter.

The real issue was simpler and more insidious. Hypatia represented everything the new Christian order opposed. She was a woman with public authority. She taught ideas that weren't Christian. She had influence over powerful men. She refused to marry or submit to male guardianship. She wore the robes of a philosopher and walked through the streets debating with men as an equal. Every aspect of her existence challenged the patriarchal, religiously uniform society that figures like Cyril wanted to create.

In March 415 CE, during the season of Lent, a mob of Christian zealots ambushed Hypatia's chariot as she traveled through Alexandria. Contemporary accounts suggest the attack was organized, not spontaneous. They dragged her into a building identified as a church (possibly the Caesareum). They stripped her naked, a deliberate act of humiliation meant to destroy her dignity. Then they murdered her, with sources describing the weapons as roof tiles, pottery shards, or oyster shells. Her body was dismembered and burned.

This wasn't random violence. It was a public execution designed to send a message: women who stepped outside their assigned roles, who claimed intellectual authority, who refused to submit to male religious leadership would be destroyed. The fact that her killers stripped her before murdering her underscores the gendered nature of the violence. They weren't just killing a rival philosopher. They were punishing a woman who had dared to claim equality with men.

The murder shocked many contemporaries, even those with no particular love for pagan philosophy. Socrates Scholasticus, a Christian historian writing shortly after the event, was clearly disturbed by what happened. He wrote that the murder "brought no small disgrace upon Cyril and the church of Alexandria" and described it as resulting from jealousy and envy of Hypatia's influence.

But no one was punished. Orestes, who had valued Hypatia's counsel, was powerless to bring her killers to justice. Cyril's political power protected them. Some historical sources suggest Cyril was directly responsible for inciting the murder, though this remains debated. What's undeniable is that he created the atmosphere in which such violence became possible and acceptable.

Orestes was horrified but powerless to bring Hypatia's murderers to justice. Cyril's political power protected the killers. The message was clear: intellectual independence and religious tolerance had no place in the new Christian order.

Hypatia's death marked a turning point for Alexandria. The city's tradition of open philosophical inquiry never fully recovered. Scholars became more cautious, focusing on work that wouldn't threaten religious authorities. The great era of Alexandrian mathematics and astronomy gradually faded.

Yet Hypatia's legacy persisted. Her students, many of whom became bishops and church officials, continued to revere her memory. They preserved stories of her brilliance and character. Synesius of Cyrene, one of her most devoted students who became a Christian bishop, wrote letters to her that survived and provide valuable insights into her teaching and personality.

Through the centuries, Hypatia became a symbol. For advocates of women's education, she proved that women could excel in mathematics and philosophy if given the opportunity. For defenders of reason against religious extremism, she represented the martyr of free inquiry. For those concerned about the relationship between religion and science, her murder exemplified the dangers when dogma overrides rational thought.

The Enlightenment rediscovered Hypatia with particular enthusiasm. Eighteenth-century philosophers held her up as proof that the "Dark Ages" following Rome's fall represented a genuine loss of knowledge and tolerance. Voltaire wrote about her. Feminist thinkers claimed her as an early champion of women's intellectual equality.

Modern historians debate various aspects of Hypatia's story. Some argue that religious conflict has been overemphasized and that her murder was more about political rivalry between Orestes and Cyril. Others point out that we shouldn't romanticize ancient Alexandria as some haven of tolerance, as it had its share of violence and prejudice even before Christianity's rise.

But certain facts remain undisputed: Hypatia was extraordinarily accomplished in mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy. She achieved this despite living in a society that offered women almost no educational opportunities. She commanded respect from the most powerful men of her era. And she was murdered not for anything she did wrong, but for who she was: an independent, brilliant woman who refused to be silent.

Hypatia's story resonates because the issues she faced haven't entirely disappeared. Women in STEM fields still encounter barriers their male colleagues don't face. The tension between scientific inquiry and religious or ideological dogma remains a live concern in many societies. The question of who gets to pursue advanced education and on what terms continues to generate debate.

When we look at statistics showing women underrepresented in mathematics, physics, and philosophy, we might remember that for most of history, women were formally excluded from these fields. Hypatia wasn't just an exception; she was someone who succeeded despite a system designed to prevent her success.

Her commitment to rational inquiry also offers lessons. Hypatia lived in tumultuous times when religious and political factions demanded loyalty and conformity. She maintained her independence, taught her students to think critically, and refused to compromise her principles. That stance ultimately cost her life, but it also ensured that her memory would inspire future generations.

Perhaps most importantly, Hypatia reminds us that brilliance appears in unexpected places and that artificial barriers to education and achievement don't just harm individuals but impoverish entire societies. Alexandria lost not just a mathematician but a teacher whose students might have preserved and extended Greek learning through the chaotic centuries ahead. The world lost contributions Hypatia might have made if she'd lived to old age.

Hypatia of Alexandria was neither a perfect saint nor simply a victim. She was a complex person who lived in complicated times, someone who made deliberate choices about how to live her life and what principles mattered most to her.

She chose mathematics and philosophy over marriage and children, understanding this was her path. She chose to teach publicly and maintain friendships across religious lines, knowing this made her vulnerable. She chose to advise government officials and speak her mind, aware that powerful people resented her influence.

These choices led to her murder, but they also led to a life of extraordinary achievement and influence. Sixteen centuries after her death, we still remember her name and celebrate her contributions. We remember her not just as a brilliant mathematician but as someone who proved that gender shouldn't determine who gets to pursue knowledge.

The next time you hear someone doubt whether women can excel in mathematics or science, remember Hypatia. She was solving complex equations and teaching philosophy to the Roman Empire's best minds while most of humanity couldn't read. She did this without modern resources, institutional support, or a society that believed women capable of such achievement.

If Hypatia could accomplish what she did against those odds, imagine what women can achieve when artificial barriers are removed. That might be her greatest legacy: not just what she accomplished, but what her example suggests about human potential when we stop limiting who gets to use their gifts.

Hypatia of Alexandria was a 4th-century mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who became head of Alexandria's prestigious Neoplatonic school despite being a woman in a patriarchal society

She made significant contributions to mathematics and astronomy, writing commentaries on major works and improving astronomical instruments and tables

Hypatia taught publicly and advised government officials, breaking every social convention about women's roles in ancient society

Her murder in 415 CE by a Christian mob was motivated by religious extremism and political rivalry, marking a turning point for Alexandria's intellectual culture

Hypatia's legacy demonstrates both what women can achieve when given educational opportunities and the dangers when dogma overrides rational inquiry

You liked this blog post and don't want to miss any new articles? Receive a weekly update with the best philosophy memes on the internet for free and directly by email. On top of that, you will receive a 10% discount voucher for your first order.

Your cart is currently empty.